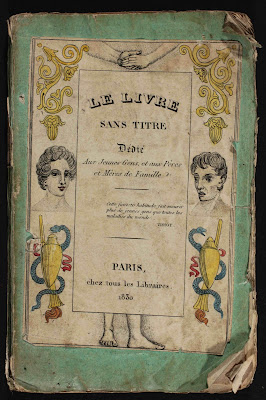

At the recent 2011 meeting of the American Association for the History of Medicine in Philadelphia I picked up a curious tract on the perils of self-abuse, or onanism. Merely speaking the word in polite company invited rebuke in the nineteenth century, so the author simply entitled his work "The Book without a Title," or Le Livre Sans Titre. It's dated 1830 and is distinguished by the charming (may I use that word in this context?) hand-colored depictions of the progressive physical (and moral) decline of the young man in question. A cautionary morality tale indeed! I've translated the captions from French to English, but words are hardly necessary to capture the flavor and tenor of this work...

He was young, handsome; his mother's fond hope

He corrupted himself!... soon he bore the grief of

his error, old before his time... his back hunches...

A devouring fire sears his gut;

he suffers horrible stomach pains...

See his eyes once so pure, so brilliant;

they are extinguished! a fiery band envelops them.

He can't walk any more... his legs give way

Hideous dreams disturb his slumber...

he cannot sleep...

His teeth rot and fall out...

His chest burns... he spits up blood...

His hair, once so lovely, falls as if from old age;

his scalp grows bald before his age....

He hungers; he wants to satiate his appetite;

food won't stay down in his stomach...

His chest collapses... he vomits blood...

Pustules cover his entire body... He is terrible to behold!

A slow fever consumes him, he declines;

all of his body burns up...

His entire body stiffens!... his limbs stop moving...

He is delirious; he stiffens against death;

death gains strength...

At the age of 17, he expires, and in horrible torment

The only library listing for this book in WorldCat is the British Museum. But then again, if you can't give a book a title, it might prove pretty hard to find! We're happy to have it as part of the library for the Percy Skuy Collection at the Dittrick.

Jim Edmonson